“No One Believed Me”: A Global Overview of Women Facing the Death Penalty for Drug Offenses

“No one believed me” is a quote from Merri Utami, who was sentenced to death for drug trafficking in Indonesia in 2002. Her quote reflects the injustices faced by women accused of capital drug offenses around the world: many decision-makers disbelieve women’s plausible innocence claims or discount the effects of relationships and economic instability on women’s decisions to traffic drugs.

COVER PHOTOGRAPH: Mary Jane Veloso, on death row in Indonesia for a drug offense, being escorted by police in 2015.

Table of Contents

Profile: Merri Utami (Indonesia) 11

Gender, Drug Crime, and International Law. 13

The Use of the Death Penalty for Drug-Related Offenses: A Review of State Practices. 15

Profile: Ejaz Fatima (Saudi Arabia) 18

Gendered Pathways to Offending.. 20

The Role of Economic Insecurity in Pathways to Drug Offending. 20

Manipulative Relationships. 22

Implications for Criminal Legal Processes. 28

Gender Bias and Fair Trial Violations. 31

Profile: Mary Jane Veloso (Indonesia) 40

Profile: Siti Aslinda Binte Junaidi (China) 55

Policy Recommendations to Stakeholders. 60

In States That Apply the Death Penalty for Drug-Related Offenses. 60

In States That Do Not Punish Drug-Related Offenses with Death. 61

Acknowledgments

The co-authors of this report are Charlotte Andrews-Briscoe, Laura Ann Douglas, Ariane Jacoberger, Delphine Lourtau, and Hailey Shapiro. Charu Kulkarni, Pongnut Thanaboonchai, and Xiaoyu Xin contributed substantive research. Many thanks to Maci East, Randi Kepecs, and Marilyn Vaccaro for proofreading the report, and to Professor Sandra Babcock, who meticulously edited each chapter.

A very special thank you to our partner Harm Reduction International for helping us gather resources to produce this report, and for their close collaboration and expert guidance throughout the drafting process.

We are immensely grateful to the many individuals and organizations who shared their time, knowledge, and insights with us. We are deeply indebted to the individuals featured in our case studies, and their families and lawyers for allowing us to present their stories. We are especially thankful to Merri Utami—a woman currently on death row in Indonesia—for contributing a prologue to this report, and to Naomi Burke-Shyne of Harm Reduction International for contributing a foreword to this report. We are very grateful to our local partners who collected hard-to-find data and shared countless insights in personal interviews. Without their contributions, this publication would not have been possible. We are particularly indebted to the following organizations and individuals:

Our partners that conducted on-the-ground investigations that informed our report

Komnas Perempuan (the National Commission on Violence Against Women): Komnas Perempuan is a national human rights institution in Indonesia dedicated to the eradication of all forms of violence against women. Komnas Perempuan carries out monitoring, fact-finding and reporting on situations related to women’s human rights and provides advice and recommendations regarding policy to state institutions and community organizations. We especially thank Yuni Asriyanti for her help.

LBH Masyarakat: LBH Masyarakat is a not-for-profit non- governmental organization, based in Jakarta, Indonesia that provides free legal services for the poor and victims of human rights abuses, including people facing the death penalty or execution; undertakes community legal empowerment for marginalized groups; and advocates for law reform and human rights protection through campaigns, strategic litigation, policy advocacy, research and analysis

Reprieve: Reprieve is an international legal action charity registered in the United Kingdom. Reprieve provides free legal and investigative support to those who have been subjected to state-sponsored human rights abuses; protects the rights of those facing the death penalty; and delivers justice to victims of arbitrary detention, torture, and extrajudicial killing. We especially thank Catriona Harris, Peter John, and Teresa Prasetio for their help.

Our partners who provided expert help

The Anti-Death Penalty Asia Network: The Anti-Death Penalty Asia Network is a regional network of organizations and individuals committed to working towards abolition of the death penalty in the Asia Pacific. Our role is to create wider societal support for abolition of the death penalty in the Asia Pacific region through advocacy, education and network building. We especially thank Ngeow Chow Ying and Dobby Chew for their help.

Justice Project Pakistan: Justice Project Pakistan is a legal action non-profit organization based in Lahore, Pakistan. It provides direct pro bono legal and investigative services to the most vulnerable Pakistani prisoners facing the harshest punishments, particularly those facing the death penalty, the mentally ill, victims of police torture, and detainees in the War on Terror. JPP’s vision is to employ strategic litigation to set legal precedents that reform the criminal justice system in Pakistan. It litigates and advocates innovatively, pursuing cases on behalf of individuals that hold the potential to set precedents that allow those in similar conditions to better enforce their legal and human rights. Its strategic litigation is coupled with a fierce public and policy advocacy campaign to educate and inform public and policy-makers to reform the criminal justice system in Pakistan. We especially thank Sana Farrukh for her help.

Professor Zhiyuan Guo and Rong Ma of the Center for Criminal Law and Justice at the China University of Political Science and Law.

We are thankful for our close collaboration with experts at the Thailand Institute of Justice. We are also grateful to the following experts for their invaluable assistance: Dr. Teng Biao, Damien Chng, Joanna Concepcion (Migrante International[1]), Imogen Rogerson Costello and Nicola Macbean (The Rights Practice), Josalee Deinla (the National Union of Peoples Lawyers), The Dui Hua Foundation, Jennifer Fleetwood (Goldsmiths College), Lucy Harry (Centre for Criminology at Oxford University), Sara Kowal (Eleos Justice at Monash University), Samantha Jeffries (the School of Criminology and Criminal Justice at Griffith University), Doriane Lau and Joshua Rosenzweig (Amnesty International), Merethe Macleod and Cyril Poulopoulos (the Great Britain China Centre), Hossein Raeesi (capital defense attorney from Iran), M Ravi and Gabriel Rafferty (KK Cheng Law LLC), Datuk N. Sivananthan (defense attorney), Tobias Smith (scholar on capital punishment in China), sources in the Thai judiciary, James Suzano (Director of Legal Affairs at ESOHR), Monica T. Whitty (UNSW Institute for Cyber Security), and Gloria Lai, Marie Nougier and Coletta Youngers (International Drug Policy Consortium).

Many thanks for assistance from Professor Florence Bellivier, Professor Chan Wing Cheong, Glorene A. Das (Tenaganita), Sangeet Kaur Deo (defense attorney), Kirsten Han (Transformative Justice Collective), the House of Blessing Foundation, Andrew Jefferson and Ergun Cakal (DIGNITY), Jutathorn Pravattiyagul, Juliette Rousselot and Andrea Giorgetta (FIDH), Vanida Thepsouvanh (Lao Movement for Human Rights), Dr. Diana Therese M. Veloso, and experts from the United Nations Development Programme.

In addition, we want to express our thanks to sources who wish to remain anonymous but provided us with critical help.

We are deeply appreciative of our support from the Human Rights Initiative at the Open Society Foundations. Its contribution made this report possible.

The Cornell Center on the Death Penalty Worldwide takes sole responsibility for the final content of the report.

Prologue

Merri Utami is on death row in Indonesia for drug trafficking. She maintains that she had no knowledge of the drugs she was carrying. We feature Merri’s story in greater detail in this report’s first case profile.

My name is Merri Utami. Twenty years ago (this October) I was sentenced to death for a drug offense. I have spent 20 years in prison for an act I did not understand at the time. During this long imprisonment, I have suffered a lot. I still remember how the media covered my case when I was arrested and dubbed me the ‘Queen of Heroin.’ I had no chance to tell the truth. I still remember that during the police investigation stage I said repeatedly that the drugs were not mine, but no one was there to help me, and no one believed me. They tortured me, but even then I would not confess.

At the moment the judges sentenced me to death, I could not control my emotions. I was terrified. After that, there were moments when I felt like I wanted to die. But my most challenging moment was when I had to convey the judge’s verdict to my family. My children would grow up without a mother, and I couldn’t bear the shame my family would have to endure due to my case. The greatest pain of all was when my son died. It was his birthday, and I wanted to call him from prison, but I didn’t have the money to pay for the call. I ended up selling water spinach, and I only managed to collect the money three days after my child’s birthday. The day I finally got to call my son, they had just buried him. My chest felt like it was smothered, because I could not run and hug his body. The yearning for my child still makes my heart shudder. His death urged me to rise above my adversity and begin to accept my situation. I learned that an imprisoned soul can still express itself. A well-grown tree can produce fruits and enlighten the mood of people who care for it. I have tried to learn to be like a tree, through singing, gardening, and helping to build a church within the prison. But at times I have been in a place of desperation. For eight months, I did not have money to buy the basic needs of a woman. I had to hoe and plant vegetables in exchange for sanitary napkins.

My routine work kept my mind busy until one night, in 2016, two prison guards woke me up and told me that they were taking me to Nusakambangan, the site of executions. I looked at the cell once inhabited by the late Rani Andriani, another woman sentenced to death for drug offenses who had faced the same situation I was facing now. I was so scared. Memories of the smells, sounds, and footsteps of officers in Nusakambangan still linger in my head to this day. Ahead of my scheduled execution, I was met by my daughter who brought along my infant grandchild. It was the height of my sorrow. I tried to reassure my daughter but inside my heart ached. I wanted to live and to share my experiences, so that no other vulnerable woman would be manipulated. That night, God let me stay alive.

I want the world to understand that when women are in a toxic relationship—as I was—society does not support her, but blames her for choosing the wrong man. Women are vulnerable to being manipulated by men because women feel they need protection, and most of those who provide protection are men. Even when women have been hurt over and over again, they will continue to apologize. This weakness makes women vulnerable to being tortured by men physically and mentally. I hope anyone who reads this report could take heed of these valuable lessons. I also hope that policy-makers will be wiser in assessing the deterrent effect of imprisonment. The death penalty should be abolished, because God gives people the opportunity to repent when they are at fault.

I want the world to know that we, women on death row, are suffering inwardly. Women often keep their struggles to themselves, even though they are unconsciously destroying themselves. But people can, and must, learn from the experiences of women. So women must open up and tell their stories. This is our story.

Merri Utami

July 21, 2021

Cilacap Correctional Institution

Merri Utami inside the church she helped to build in prison. Photo courtesy of LBHM.

Foreword

Executions for drug offences reached a 12-year global low in 2020, an outcome which is undermined by the steadily rising number of death sentences for drug offences being handed down by judges. Although recognised as a violation of international human rights law, the death penalty for drug offences remains a politically sensitive topic, to the point that it is a recurring theme for presidential posturing in a handful of countries around the world.

This important study takes a deep dive into the experiences of women on death row for drug offences. Significantly, this report examines the issue at a time when globally, women’s incarceration rates have increased by 17% since 2010 (a disproportionally higher increase than men); with punitive drug laws as a major driver of this trend. It is estimated that approximately 35% of women in prison around the world have been convicted for drug offences. In the Middle East and Asia, drug offences are the second most common crime for which women are sentenced to death.

The war on drugs narrative justifies the harshest punishments for drug-related crimes, and – as highlighted in Harm Reduction International’s global research – in 35 countries the harshest judicial punishment means the death penalty. People on death row for drug offences tend to be involved at the lowest level of the drug trade, and are generally marginalised in society. Gender, socio-economic position, ethnicity and foreign status in a country add intersectional vulnerability to this context. I note the authors’ interest in also amplifying the experiences of transgender and gender non-binary people on death row for drug offences, which was limited by the paucity of information available; and acknowledge the additional vulnerabilities of a group of individuals whose stories are largely hidden from the public.

While some women engage in the drug trade through their own volition, for others, a narrower range of choices, along with poverty, coercion, violence, manipulation, and the survival needs of a family play a significant factor in their involvement. Merri Utami’s case and her campaign for clemency shows how she ended up on death row after being manipulated by people with more power and resources.

However, notwithstanding the often blatant reference to gender in judicial proceedings, an analytical approach to the role of gender and connected vulnerabilities is often omitted from consideration when it comes to sentencing. The cases documented by Cornell Center on the Death Penalty Worldwide demonstrate the alarming extent to which women sentenced to death for drug offences experienced gender bias in criminal proceedings and violations of their right to a fair trial.

We thank the Cornell Center on the Death Penalty Worldwide for its work to shine a light on the lives of women on death row for drug offences and are committed to working together to challenge the harms of, and limitations of our archaic laws, policies and processes. We must strive for societies where it is inconceivable that our elected representatives tolerate the death penalty, or invest vast amounts of tax payer dollars in systems which sustain state violence and mass incarceration. We can only begin to address the harm done by firmly connecting our work towards abolition of the death penalty with the full decriminalisation of drugs and inclusive feminist movements.

Naomi Burke-Shyne

Executive Director

London, July 2021

Harm Reduction International

Executive Summary

The punitiveness of the international drug control system has been largely responsible for the growth of the world’s female prison population in the last three decades. In countries that punish drug offenses with death—a violation of international law—a large majority of the women on death row were convicted of drug-related offenses. This report examines the circumstances that lead women to commit or be charged with drug offenses and the impact of gender bias on the criminal process they experience.

Drug convictions account for a minority of the world’s death sentences but a majority of capital convictions in a small number of so-called ‘retentionist’ death penalty states. Capital drug laws are most entrenched in states that resist the global trend towards abolition, concentrated in Asia and the Middle East. Many of these states do not publish information on their use of capital punishment. Moreover, gender-disaggregated and gender-specific data frequently does not exist. Nevertheless, this study examines the available information, notably for countries such as Indonesia, Malaysia, China, and Thailand. Our analysis reveals the following trends relating to women facing death for drug offenses:

Foreign nationals are over-represented among women on death row for drug offenses. These disparities are more pronounced among the female death row population than among death-sentenced men. Many of these foreign nationals are migrant workers. For example, in Malaysia, 95% of the 129 women on death row for drug offenses in 2019 were foreign nationals.

Economic insecurity

The gendered financial burden of caring for family members, especially among women with little education and without the aid of strong social support systems or access to stable work, is one of the key factors that pushes women into trafficking drugs. Courts often fail to take into account women’s economic instability and caregiving responsibilities before imposing death sentences. One woman in China, a single mother, spent the proceeds of a drug sale to care for her son, who had a disability. The court held that this fact was irrelevant. Although economic need often propels women into drug trafficking, women typically make little money from trafficking (they are often unaware of what exactly they are carrying). Drug trafficking is, like most women’s jobs pre-arrest, just another precarious job—albeit one that exposes them to the risk of capital punishment.

Manipulative or coercive relationships with male co-defendants.

In many of the cases we reviewed, women transported drugs under the influence or pressure of a male partner, who typically suffered fewer or no criminal consequences. In part, this reflects the gender-stratified and male-dominated structure of the drug economy. In one case, the only apparent evidence against the spouse of a drug trader who was well-known to the police was an informal ledger that included the word “wife.” She was sentenced to death; her husband disappeared before serving any jail time.

Women are also disproportionately likely, compared to men, to fall victim to online romance scams that may ultimately lead them to unwittingly traffic drugs. Men who fake relationships to trick women into transporting drugs rely on a common set of tactics, but female defendants struggle to convince judges that they were not aware of the drugs they were carrying. Courts also often neglect to consider the role of an abusive relationship on a woman’s decision to transport drugs.

Refusal to consider gender-specific mitigation

Fair trial principles dictate that courts should consider all relevant mitigating circumstances before imposing a sentence. In practice, however, many courts neglect gender-specific mitigation, and in states that impose a mandatory death penalty, courts may not consider any mitigating circumstances at all. Our research suggests that past trauma from abusive relationships affects the trajectories of many women who traffic drugs. Available data also suggests that women in prison for drug offenses are more likely than men to have endured adverse childhood experiences. Nevertheless, courts routinely fail to take into account the impact of trauma and gender-based violence in determining the appropriate sentence for women.

Reliance on stereotypical gender narratives

In the course of this study, we uncovered many cases where courts relied on gender stereotypes to interpret women’s circumstances and motivations before sentencing them to death. They offer troubling indications that gender bias affects outcomes in capital drug cases. Notably, courts are reluctant to accept that a female defendant was tricked or pressured into transporting drugs unless she matches the profile of a helpless female victim: poor, uneducated, and—in cases involving a male co-conspirator–inexperienced with men. Courts tend not to believe that women from less disadvantaged backgrounds or who have experienced prior romantic relationships are vulnerable to coercion or manipulation. In one case from Malaysia, the court concluded that “it is very unlikely that the respondent, who is a diploma holder… could have placed herself in a situation where she could be exploited to commit a crime.” In the case of another woman, who claimed her partner manipulated her into transporting drugs, the court described the defendant’s defense posture as “a damsel in her maiden love,” a perspective it rejected given that “she herself gave evidence that she was in the process of divorcing her husband and, on top of that, they have a child. Thus, it would not be too remote in finding that she fully knew the effect, danger and pitfall of anyone madly and blindly in love.”

Reliance on legal shortcuts to conviction and sentence

In some countries with punitive drug laws, courts are precluded from examining the circumstances of the offense or the offender before deciding on the appropriate sentence. In Malaysia, a death sentence is mandatory for defendants who are convicted of drug trafficking, no matter what mitigating factors exist. In many jurisdictions, moreover, the law provides courts with two major shortcuts to conviction: a defendant in possession of a drug is presumed to know what she is carrying; and if the quantity of drugs is above a statutory minimum, she is presumed to intend to traffic drugs. These legal rules dramatically increase the number of women who are sentenced to death while ignoring women’s position in the drug trade’s gender-stratified and predominantly masculine system. Women are disproportionately likely to be low-level drug couriers—and therefore ignorant of the type, quantity, and value of the drugs they are carrying.

Lack of access to adequate interpreters and lawyers

Women in many migrant source countries tend to have less access to education than men, which makes them less likely to speak a foreign language. Because of disparities in socioeconomic status and educational attainment, women struggle more than men to access an interpreter or retain skilled legal counsel. In one case we reviewed, the woman’s boyfriend and potential co-defendant told the police, in a language she did not understand, that she did not need an interpreter, before pinning the blame on her and walking away—while she was condemned to death.

This report relies on primary and secondary data sources and is the first effort to aggregate global data surrounding drug offenses and the death penalty as these phenomena relate to gender. Based on our findings, we have issued a series of urgent recommendations to governments, lawmakers, the judiciary, prison authorities, and civil society. We hope that this report spurs further research and attention to the plight of women facing death sentences for drug-related offenses.

Introduction

In our previous research report about women on death row globally, Judged for More Than Her Crime, we highlighted gender discrimination in capital trials and the uniquely precarious detention conditions for women facing capital sentences. Here, we use a gender lens to focus on women facing the death penalty for drug offenses.

Scholars and commentators have observed that the “number of women arrested for participating in the illicit drug trade is on the rise worldwide, in particular among women who lack education or economic opportunity or who have been victims of abuse.”[2] Criminologists attribute this rise to harsher sentencing for low-level drug offenses, rather than increased criminal activity by women.[3] As a whole, the use of the death penalty is on the decline, but a small minority of nations have passed legislation expanding the application of the death penalty for drug offenses.[4] Other countries are attempting to bring back the death penalty for use in drug cases.[5] The use of the death penalty for drug crimes is of special concern because it violates international law, which requires that the death penalty be used only for the “most serious crimes,”[6] a threshold that human rights bodies have repeatedly found that drug offenses do not meet.[7]

In this report, we dove deep into the pernicious ways in which women experience the disparate impact of capital drug laws. Most notably, we found that the economic insecurity that women experience, their disproportionate share of caretaking responsibilities, and manipulation or coercion by intimate partners result in women committing drug offenses or being charged with drug offenses in countries where they face the death penalty. The drug trade is a gender-stratified and predominantly masculine system,[8] and men commit most drug crimes.[9]

Some women make a conscious decision to traffic drugs in context of their gendered positionality. Within the gender-stratified drug trade, many other women are tricked into carrying drugs unwittingly, and many of those women are targeted by men who became their trusted, intimate partners under false pretenses before asking women to transport items that contain drugs.[10] Available data suggests that the top of the drug trade hierarchy is male-dominated, and that relative to their overall role in the drug trade, women are disproportionately likely to be low-level drug couriers.[11] A number of countries mandatorily impose the death penalty for certain drug offenses, unless defendants are able to provide valuable information that allows law enforcement to disrupt the drug trade.[12] This means that low-level couriers, and therefore women, are disproportionately unlikely to have this information, and therefore more likely to receive the mandatory death penalty without the opportunity to present compelling mitigation.[13]

Researcher Samantha Jeffries has concluded that women incarcerated for drug offenses in Thailand have experienced “trauma, disordered family lives, other adverse life experiences, deviant friendships, addiction (and other mental health problems), male influence and control, limited education, poverty, and familial caretaking responsibilities.”[14] Our research suggests that many women on death row for drug offenses around the world share these characteristics. These challenges are heightened in the lives of women who are noncitizens, who are disproportionately sentenced to death in at least three of the countries profiled in this report. Many of them are migrant workers who face “compounded vulnerabilities.”[15]

Our research has also uncovered examples of gender bias in the criminal legal system, such as courts that, in capital drug trials, focus on a female defendant’s history of sex work, and police who impute guilt to a woman based solely on her male co-defendant’s accusations.[16] Courts routinely fail to take into account the impact of trauma and gender-based violence in determining the appropriate sentence for a woman’s case.

As in our previous work, we highlight both the serious risk that innocent women are sentenced to death for drug offenses, and the sympathetic stories of women who are guilty of their offenses—but whose guilt is mitigated by compelling circumstances. Feminist academics emphasize the importance of acknowledging that women often have agency in choosing to traffic drugs and that some women participate at all levels of the drug trade,[17] and we aim to reflect the complex, gendered realities within which some women make their decisions. As a result of media bias towards narratives of innocence and our desire to profile women only when attention on their case would not harm them, our report includes multiple stories of women who have compelling arguments that they are innocent. We wish to emphasize, however, that both innocent and guilty women sentenced to death for drug offenses deserve fair trials and sentencing proceedings in which the realities of their lives receive full consideration.

Methodology

As we have previously noted, data regarding women sentenced to death around the world is scant.[18] In compiling this report, we relied on a variety of sources, including empirical studies, reports, journal articles, government statistics, complaints to international human rights bodies, case files, country-specific legislation, jurisprudence, civil society, and media reports. In addition, we conducted interviews with country experts from China, Indonesia, Iran, Malaysia, Pakistan, the Philippines, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, and Thailand.

Whenever possible, our report drew on information specific to women on death row for drug offenses. Where such information was not available, we relied on information about women incarcerated for drug offenses who faced a possible death sentence at trial, or women incarcerated for drug offenses more generally. We indicate these distinctions in the text of the report.

We define drug offenses as “drug-related activities categorised as crimes under national laws… [T]his definition excludes activities which are not related to the trafficking, manufacturing, possession or use of controlled substances and related inchoate offences (inciting, assisting or abetting a crime).”[19]

We have relied on both qualitative and quantitative data. We privileged in-depth profiles of individual women and used their narratives to contextualize our research. We strove to adopt an intersectional lens, and we were guided by research on intersectional discrimination that highlights the importance of using women’s narratives about themselves.[20] For this reason, long-form profiles of women with lived experience of incarceration and capital sentencing are central to our report.

Our research drew heavily on information gathered by in-country experts—including practicing capital defense lawyers, activists, academics, and non-profit organizations working on issues related to the death penalty, gender rights, migrant worker rights, drug policy, extrajudicial killings, and female incarceration. Our partners’ knowledge of the legal, political, and cultural systems in which they work is invaluable, and is based on their first-hand experience as well as their engagement with a wide range of stakeholders in the criminal legal system, including civil society, prison administrators, and individuals living under a death sentence.

Gathering information on death penalty practices is challenging at the best of times, and the COVID-19 pandemic further curtailed our access to information. Our partners were often unable, during the research period, to visit prisons and carry out their usual work with directly impacted women. In several cases, therefore, we had to rely on information that dates from before the pandemic, and we tailored our country research to the available information.

Finally, we started our research with the goal of incorporating all gender minorities into our study, including individuals who identify as cis-women, trans women, trans men, and non-binary. We found, however, that there is little to no publicly available information about trans and non-binary individuals facing the death penalty for drug offenses. We have shared what information we could find about trans and non-binary people (though only some identify as women). Until more death penalty advocates engage with the rights of trans and non-binary people, studies on gender and capital punishment will be limited largely to cis- women.

Profile: Merri Utami (Indonesia)

Merri Utami is a grandmother who has spent 19 years on death row in Indonesia. Merri was convicted of illegally importing drugs into Indonesia, but she insists that she had no knowledge of her role, and that she was in fact targeted and manipulated by professional drug traffickers. Merri’s life has been shaped by poverty, abuse, and exploitation.

Merri Utami in prison in 2016, during her first meeting with LBHM. Photo courtesy of LBHM.

At a young age, Merri entered an abusive marriage.[21] Her husband was a violent man, but Merri felt she did not have the power—or the financial means—to leave him.[22] More than twenty years later, the marks of his violence remain on Merri’s body.[23] They had two children: Yosi, a son, and Devi, a daughter. Yosi was born with a defective heart valve, and the cost of his treatment consumed much of the family’s meager resources.[24] Merri’s husband was a gambler, and his debts added to the family’s financial stress. Pressured by her husband, and the need to treat her son, Merri left Indonesia to work as a domestic worker in Taipei.[25] Her children went to live with an aunt in East Java.

Merri missed her children desperately and she wrote long, loving letters to them, trying to parent from afar.[26] She returned home to Indonesia once, hoping that she could stay, but Merri’s husband had not reformed and his beatings resumed.[27] She quickly returned to Taipei, and they separated. After some time, an acquaintance in Taipei introduced her to Jerry, who presented himself as a Canadian businessman living in Jakarta. They began a relationship. While her husband had been vicious, Jerry was kind.[28]

One day, Jerry surprised Merri with tickets to Nepal. He told her that they would go on holiday and afterwards they would marry.[29] After a few days in Nepal, Jerry unexpectedly announced that he had to return to Indonesia early for work. He apologized profusely and encouraged her to enjoy the rest of her holiday.[30] Jerry said that Merri’s purse was too old and that, as an apology for his departure, he had instructed a friend to gift her a new one.[31] When Jerry’s friend gave Merri the bag, she asked why it was so heavy. Jerry’s friend explained that it was a good quality bag, which was heavier than a cheap bag, and Merri believed him.[32]

Merri returned to Indonesia, and left the airport carrying the new purse. She quickly realized that her suitcase, which had her souvenirs from Nepal inside it, was missing, and she returned to the airport to report her suitcase missing. Upon re-entering the airport, security officers put all of Merri’s luggage through X-ray scanners and then, swiftly, led her into a small room, placing the new purse from Jerry on a table. The officers pricked the bag with a needle, and white powder started pouring out.[33] The lining of the bag was stuffed with heroin. Merri was shocked, and tried to call Jerry for help, but his phone had been disconnected.[34] Two police officers escorted Merri to a hotel where they interrogated her. Merri insisted that she had no knowledge of the drugs. The police held a gun to her head, kicked her in the face and slapped her, leaving her with a split lip and wounds covering her body.[35] Despite their brutality, she refused to confess.

Because Merri could not afford a lawyer, she was assigned one by the government.[36] At her trial, her lawyer did not present a single witness or expert to testify on her behalf.[37] He failed to tell the court about Merri’s background of domestic violence or explain her isolation and vulnerability to exploitation as a migrant domestic worker.[38] The all-male panel of judges observed that Merri’s testimony was fractured and unclear.[39] They reasoned that this was indicative of her role in a highly secretive international drug syndicate,[40] instead of considering that it might in fact reflect the effects of trauma.[41] The judges also deemed that Merri did not look sufficiently remorseful.[42] On May 20, 2002, Merri was convicted of importing heroin and sentenced to death by firing squad.[43] (This verdict was later upheld by Bandung High Court in 2002 and the Supreme Court in 2003.)[44]

Shortly after her conviction, Merri received the news that her son, Yosi, had died. She said she felt as though her “chest was… smothered.”[45] Meanwhile, she continued to face daily indignities as a woman within the prison system. Nonetheless, Merri strived to make her life bearable. She learned to garden and became an active church member.[46] Merri explains that she was trying “to make peace with the unimaginable environment.”[47] In 2005, Merri was reunited with her daughter, Devi, and the two restored the bond that had been damaged by Merri’s incarceration.[48]

One night in 2016, prison guards informed Merri that she was to be transferred to Nusa Kambangan, known as “Execution Island.”[49] Devi frantically called Merri’s lawyer, but he did not return her calls.[50] The Community Legal Aid Institute (LBHM) heard about Merri’s case, and offered her their legal services.[51] They rushed to submit a clemency petition to the Indonesian President just days before her scheduled execution.[52]

Merri and her daughter, Devi, before Merri’s incarceration. Photo courtesy of LBHM.

The night before Merri was due to be executed, Devi came with her infant child to say goodbye to her mother.[53] Merri describes that moment as “the height of [her] sorrow.”[54] On July 29, 2016, four people who at been imprisoned with Merri were executed, but Merri was spared.[55] Five years later, however, Merri remains in prison under sentence of death. Her request for clemency has gone unanswered.[56]

To write this profile, we conducted interviews with Merri’s lawyers, and consulted court records and publicly available information. We publish this profile with Merri’s consent.

Global Trends

Gender, Drug Crime, and International Law

The prohibition of capital punishment for drug offenses under international law

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), one of the most widely ratified human rights treaties, restricts the use of capital punishment to the “most serious crimes.”[57] In the last 30 years, treaty bodies, human rights courts, and scholars have interpreted this standard as encompassing only “intentional crimes, with lethal or other extremely grave consequences.”[58] The U.N. Human Rights Committee, the treaty body tasked with interpreting the ICCPR, has repeatedly made clear that drug offenses do not meet the “most serious crimes” threshold.[59] Imposing death sentences or carrying out executions for drug crimes therefore contravenes international standards.[60]

Nevertheless, a small but vocal minority of states continues to impose capital punishment for drug offenses, often as part of punitive anti-drug policies, arguing that the drug trade creates ‘‘threats to the life, values and health of the state”—and thus meets the threshold of “most serious crime.”[61] States that use capital punishment for drug offenses claim that the death penalty has a deterrent effect on drug trafficking and drug use, although there is no evidence that it is more efficient than other methods of punishment.[62] In fact, the international drug control system, characterized by harsh punishments and police enforcement, has done little to decrease the harms associated with drug use.[63]

Globally, 35 countries currently prescribe the death penalty for drug offenses, mostly concentrated in Asia and the Middle East. States that impose the death penalty for drug offenses are more likely to belong to the minority of countries that continue to carry out executions. Only seven of the 35 countries that retain the death penalty for drug offenses are de facto abolitionist, according to the U.N.’s definition of the term (no executions in at least ten years).[64] The remaining 28 countries that punish drug offenses with death, however, belong to the group of 35 more broadly retentionist jurisdictions[65] (they have carried out at least one execution in the past decade).[66] Among these, nine states are among the world’s top ten executioners as identified by Amnesty International.[67] As a result, although the death penalty for drug offenses is a regional trend, it is one that accounts for a significant part of the world’s use of capital punishment.

In the 35 states that currently prescribe the death penalty for drug offenses, capital punishment applies to a range of drug-related activities, most notably cultivation and manufacturing, smuggling, trafficking, and importing/exporting controlled substances. Drug trafficking includes smuggling, trading, exchanging, or selling a drug.[68] Certain states also apply the death penalty for offenses such as drugs possession and drugs possession for trafficking, storing and hiding drugs, financing drug offenses, or inducing or coercing minors to use drugs.[69]

In 12 states, the legal framework compels courts to impose arbitrary death sentences as a punishment for at least certain drug offenses, in violation of international law. These states apply the mandatory death penalty for drug trafficking,[70] in many cases determining that the sentence should be death by only looking at the quantity of drugs involved. In these cases, domestic courts have no discretion to consider the circumstances of the offender or the offense before imposing a sentence of death.[71] This practice violates international law prohibiting mandatory capital sentencing.[72]

Drug laws that make possession a capital offense are particularly problematic under international law. Capital possession laws target individuals who use drugs rather than individuals involved in the drug trade. Yet six states apply the death penalty for possession of drugs, defined here as the mere act of being in possession of a substance.[73] Possession requires no intent to distribute and counts among the least serious drug-related offenses. Fourteen states[74] allow the imposition of the death penalty for possession for the purpose of trafficking. At least seven of these[75] presume intent to traffic if the defendant carried more than a threshold quantity provided by law.[76] In some countries, the amount that triggers the presumption of trafficking—which can lead to a death sentence—is very low. For example, in Sri Lanka, possession of just two grams of cocaine triggers the presumption,[77] although it is not uncommon for people who use cocaine regularly to consume one gram or more a day.[78]

The persistence of excessively retributive capital drug policies stands in sharp contrast to the abolitionist trend that has gained ground worldwide over the past three decades.[79] Between 2008 and 2018, excluding China, five of the states that retain the death penalty for drug offenses (Iran, Singapore, Indonesia, Vietnam, and Saudi Arabia) were responsible for almost 40% of total known executions.[80] While some states, such as Iran, have progressively restricted the application of the death penalty for certain drug offenses, others, such as the Philippines, have proposed reintroducing capital punishment for drug offenses.[81]

Our research indicates that, in practice, even in countries that do not have a mandatory death penalty, courts often fail to adequately consider the circumstances of the offense and the offender, including in drug cases. Courts are particularly reluctant to consider gender-specific mitigation evidence. As a result, even though women often play a minor role in the drug trade and are sometimes manipulated or coerced into committing drug offenses, they are easy targets for drug enforcement authorities. The current international drug control system has thus dramatically increased the number of women imprisoned and sentenced to death.[82]

Women sentenced to death for drug offenses under international law

Very few international standards specifically address women’s rights within the criminal legal process. International law does exclude pregnant women from the application of the death penalty, and several regional treaties exclude breastfeeding mothers.[83] These protective standards grant additional safeguards only to women in their maternal role, emphasizing the value of women who meet socially-enforced ideals of femininity.

More than a decade ago, the international community adopted standards regarding the treatment of women in prison, but they remain vastly under-implemented. The United Nations Rules for the Treatment of Women Prisoners and Non-custodial Measures for Women Offenders (the ‘Bangkok Rules’), which complement the United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (the ‘Mandela Rules’),[84] set out minimum standards for the humane incarceration of women, including facilities that separate them from male detainees and supervision by female staff.[85] Eleven years after their adoption and despite the exponential growth of the female prison population in the last 20 years, prisons remain largely designed for a male population.[86] In April 2021, recognizing the growing number of women incarcerated for drug offenses, the U.N. Office on Narcotic Drugs and Crimes, together with the Office for Rule of Law and Security Institutions in the Department for Peace Operations and the Office of the U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights, reiterated the need to take into account the distinct backgrounds and needs of incarcerated women.[87]

Image by Obilia Studio. Photo courtesy of IDPC

In recent years, international bodies have begun to recognize the need to bring a gender lens to international drug policy. In 2016, the U.N. General Assembly addressed human rights impacts of drug control and discussed gender-specific issues faced by women incarcerated for drug offenses, such as the need to access gender-sensitive health services and counseling. It called for member states to involve women in all stages of the development, implementation, and monitoring of drug policies.[88] That same year, the U.N. Commission on Narcotic Drugs called on member states to consider the specific needs of women and girls in implementing drug policies.[89]

These declarations fall short of addressing the human rights issues women face in capital drug prosecutions. In addition, the frequent unavailability of gender-disaggregated and gender-specific data impedes both national and international actors from understanding how gender bias operates in capital sentencing and finding solutions to address it.

The Use of the Death Penalty for Drug-Related Offenses: A Review of State Practices

Global trends on the use of the death penalty for drug offenses

Punitive drug policies contribute significantly to the growing prison population worldwide,[90] particularly with respect to women. In 2020, over two million people were in prison for drug-related offenses,[91] and drug-related charges accounted for 20% of the global prison population.[92] In the last 20 years, the global female prison population has increased by 50%, much of it attributable to (often low-level) drug-related convictions.[93] Moreover, punitive drug laws have a greater impact on women’s imprisonment (35% of 714,000 women globally are in prison for drugs) than on men’s (19% of ten million men).[94] This trend is most notable in countries like Thailand, where the ratio of women incarcerated for drug offenses has reached 84% of the total female prison population.[95] Women’s incarceration affects their families in unique ways: worldwide, around 19,000 children are currently living with their mothers in prison.[96]

The available data suggests that drug convictions account for a minority of the world’s death sentences but a majority of capital convictions in a small number of states. Amnesty International reports that by the end of 2020, at least 28,567 people were known to be under sentence of death, with 82% of them in only nine countries, excluding China.[97] Harm Reduction International estimates that, amongst them, at least three thousand were on death row for drug offenses (though, due to lack of transparency around death penalty data, the true number may well be higher), again excluding China.[98] In a handful of countries, however—many of which continue to carry out executions—drug convictions underlie the vast majority of capital sentences. In the states defined by Harm Reduction International as ‘high application’ death penalty states for drug offenses,[99] drug convictions account for a substantial proportion—and sometimes an overwhelming majority—of death-sentenced prisoners.[100] In 2020, 87% of all recorded death sentences in Vietnam were imposed for drug offenses,[101] and in the same year, 86% of new known death sentences in Indonesia were imposed for drug offenses.[102] Every new known death sentence in Singapore in 2019 was for a drug offense.[103]

According to Amnesty International murder and drug-related offenses underlie most of the world’s executions,[104] but precise data is exceedingly difficult to come by. The best available estimates almost certainly undercount the true number of drug-related executions globally, possibly by hundreds. Amnesty confirmed 122 known drug-related executions out of 657 executions globally in 2019 (excluding China).[105] In 2020, Amnesty documented 483 executions globally (excluding China),[106] of which 30 were drug-related.[107] This figure represents a 96% drop from the figure Harm Reduction International reported in 2015,[108] which is more likely attributable to the global pandemic rather than a shift in state policies. Given the lack of reliable data, particularly from China—which executes more people than the rest of the world combined—and Vietnam, these figures offer only a glimpse into the scale of drug-related executions and death sentences globally.

Women facing death for drug-related offenses

Murder and drug offenses account for most of women’s death sentences globally.[109] Among the eight states defined as ‘high application’ death penalty states for drug offenses (China, Indonesia, Iran, Malaysia, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam),[110] all either currently have women on death row for drug offenses, or are believed to recently have had women on death row for drug offenses, as we detail in this report. Recently, Iran raised the minimum quantity of drugs that can trigger a death sentence.[111] Multiple sources report that, before these reforms, Iran was executing a significantly larger number of women for drug-related offenses than for homicide.[112] Gender-disaggregated death row data is not available for China, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, or Vietnam.

Image by Obilia Studio. Photo courtesy of IDPC

In the remaining high application states for which we have data—Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand—we observe three trends: (1) drug offenses account for most of the known death sentences nationwide; (2) an overwhelming majority of the women on death row were convicted of drug offenses; and in Malaysia and Thailand, (3) drug convictions underlie a greater proportion of death sentences among women than among men. Amnesty International reports that, in Malaysia, 95% of all women on death row in 2019 were convicted of drug offenses, compared to 70% of the men under sentence of death.[113] In Thailand, of the 33 women who were on death row as of February 2021, 94% had been convicted of drug offenses, compared to 60% of the men on death row.[114] Between 2000 and 2018, 18 of 22 women sentenced to death in Indonesia were convicted of drug offenses.[115]

We have faced considerable difficulties in accessing information for other states. For instance, while we know that North Korea sentenced at least one woman to death for drug trafficking in 2019,[116] we were not able to gather any information on her case or other cases in the country. Similarly, we were able to identify 14 female defendants sentenced to death in China between 2015 and 2019, eight of whom received a death sentence for drug offenses, but our research suggests that the actual numbers are much higher.[117] While we know that in 2019 Saudi Arabia executed at least two women for drug offenses, both foreign nationals,[118] there is no information available about women currently on death row. Finally, in other countries we know the number of women on death row but do not know the offense for which they received a capital sentence. According to Amnesty International, globally at least 19 women were sentenced to death and 16 were executed in 2020.[119] Again, this is likely an underestimate.

Foreign nationals facing the death penalty for drug offenses

In the high application states for which we have data, foreign nationals are overrepresented on death row. Foreign nationals make up 26% of death-sentenced prisoners in Indonesia, and all of them received a capital sentence for drug convictions.[120] In Malaysia, foreign nationals represent over 40% of death-sentenced prisoners, a large majority of whom were convicted of drug offenses.[121] All five persons executed for drug offenses in Saudi Arabia in 2020 were foreign nationals.[122] Foreign nationals face particular disadvantages in criminal prosecutions: they often do not speak the language of the police or the courts and have difficulty accessing interpreters; they have little local support in navigating the criminal system; and their families are too far to contribute to the background investigation necessary for an adequate defense.[123] The overrepresentation of foreign nationals among capital defendants facing drug charges worsens the already prevalent fair trial violations in capital drug prosecutions.

In the high application states for which we have data, foreign nationals are also overrepresented among women facing the death penalty. Many of these are migrant workers.[124] In Malaysia, Amnesty International reported that 95% of the 129 women on death row for drug offenses in 2019 were foreign nationals, compared to 70% of the men.[125] In Thailand, while we lack data for death row, we know that as of 2017, 66% of incarcerated female foreign nationals had been convicted of drug-related offenses, compared to 45% of men.[126]

State-sanctioned extrajudicial killings for drug-related offenses

Although this study focuses on states that impose judicial death sentences for drug offenses, one state that has formally abolished the death penalty espouses an equally retributive model of drug policing: the Philippines. National police forces, often with the explicit encouragement of President Rodrigo Duterte, have engaged in a years-long campaign of extra-judicial killings targeting individuals who use drugs or whom they presume are involved in the drug trade.[127] The U.N. Human Rights Council has decried “alleged widespread and systematic killings” of people who use drugs and perceived drug traders as part of a nationwide ‘war on drugs.’[128] Estimates of the number of people killed range from 8,663 (as of June 2020) to over 27,000 (as early as December 2018).[129] We include the Philippines in this review because these killings result from an identifiable public policy, and because the government has attempted on multiple occasions to reintroduce capital punishment for drug offenses.

There is no publicly available information on the number of women who have become casualties of this campaign of extra-judicial killings. Tens of thousands of women, however, have registered as persons who use drugs with their local council office, as required by law,[130] and now live with a credible fear of being killed. One investigative report likened joining this “watch list” to being “targeted for assassination.”[131] Women are also indirectly affected by the ‘war on drugs.’ In the words of the Special Rapporteur on extra-judicial, summary or arbitrary executions: “[A]s the majority of the victims are men, their female partners, by virtue too of their gender-based roles, are left to confront the associated stigma, fear, insecurity and economic deprivation, in addition to the burdens of identifying and burying their dead loved ones and seeking justice.”[132]

Finally, there have been documented cases of police killing cisgender and transgender women as a result of them registering, or in some cases being involuntarily registered, for these watch lists.[133] For instance, in 2017, the police arrested Heart de Chavez, a transgender woman living in Manila, after finding her name on the watch list. De Chavez sold small amounts of drugs in order to buy food. When the police found no drugs on her, they demanded a bribe, which she could not afford to pay. Three days later, masked men in civilian clothes pulled from her house at night and shot her at point blank range, killing her.[134]

Profile: Ejaz Fatima (Saudi Arabia)

Ejaz Fatima, a Pakistani national, was executed in Saudi Arabia in April 2019 with her husband, Mustafa Muhammad, after Saudi courts convicted them of trafficking heroin.

Ejaz Fatima and Mustafa Muhammad on their wedding day in 2006. Photo taken by Mustafa’s family. Photo courtesy of Justice Project Pakistan.

Ejaz and Mustafa married in 2006 and subsequently had five children.[135] Mustafa, the sole family breadwinner, ran a small chicken shop and took on whatever extra work he could find for daily wages.[136] The couple worked hard but they struggled to provide for their family on Mustafa’s meager income, and three of their children died in infancy.[137] In addition to their surviving children, the couple cared for Mustafa’s father, who was paralyzed. Mustafa’s mother describes Ejaz as “humble and responsible… I never found a daughter-in-law like her.”[138] Ejaz and Mustafa doted on their surviving children: their daughter Bushra, born in 2010, and their son Ali Raza, born in 2011. According to Mustafa’s family, more than anything, the couple “just wanted a healthy and long life for their two children.”[139]

In 2016, Ejaz and Mustafa told their families that they wanted to make Umrah, a pilgrimage to Mecca.[140] The couple hoped, through prayer and devotion, to improve their economic situation. They arranged their trip through a friend, Waseem, who worked as a travel agent.[141] We do not know whether Ejaz and Mustafa were aware of Waseem’s involvement in drug activities, but they felt that the trip was safe enough to travel with their daughter Bushra, aged six at the time. Mustafa’s family believed that they brought her because she “was very close to her parents and she couldn’t live without them.”[142] Their younger child, Ali Raza, remained in Pakistan. On June 27, 2016, the day the family arrived in Saudi Arabia, they were arrested at an airport in Jeddah for smuggling heroin.[143]

The airport police immediately separated the family, taking Mustafa to a men’s prison and Ejaz and Bushra to the women’s section of the Dhaban Central Prison.[144] After six months, prison officials separated Bushra from her mother and detained her for over two years in a separate juvenile facility, despite her young age.[145] Neither Saudi nor Pakistani authorities notified Ejaz and Mustafa’s family of their arrest and detention.[146]

On occasional calls to their families, Ejaz and Mustafa described a criminal process rife with fair trial violations. Neither had a lawyer or an interpreter.[147] As neither spoke any Arabic, Mustafa’s father explains, “They couldn’t understand… They weren’t [even] aware, when they were convicted, [that they had received a] death sentence.”[148] Research by Human Rights Watch and Justice Project Pakistan indicates that it is exceedingly rare for Pakistani nationals (and many other foreign nationals) to receive legal representation in Saudi Arabian courts, including in capital drug cases.[149]

Meanwhile, Bushra, who was seven by that time, lived in prison-like conditions at the juvenile facility. Supervised by Saudi officials who only spoke Arabic and surrounded by Arabic-speaking youth, Bushra could not communicate at first and gradually retreated into herself.[150] She was allowed to play outside for just one hour each day.[151] Every other month, she saw her mother for 30 minutes, under strict supervision from prison guards.[152] In two years, Bushra only saw her father twice, and his shaved head and shackled limbs reportedly “terrified” her.[153] After battling with the Saudi authorities, Ejaz’s relatives traveled to Saudi Arabia to collect Bushra and she returned home to Pakistan on February 27, 2019.[154] In her last meeting with her mother shortly before she left the country, Bushra was “mostly mute.”[155]

Less than two months later, on April 11, 2019, Ejaz and Mustafa were beheaded.[156] Again, authorities failed to notify their families, who learned the news when Mustafa and Ejaz’s former cellmates were able to send word.[157] On the morning of his execution, Mustafa had asked his cellmate to contact his family and to “ask my father to forgive me.”[158] After learning of their deaths, Ejaz’s and Mustafa’s families tried desperately to repatriate their bodies to Pakistan. The Saudi authorities did not respond to or even acknowledge the families’ request for repatriation.[159] To this day, the families have not received any legal or court documents, or any death certificates, from Saudi Arabia.[160] Turning to their own government for assistance, they applied to the High Court with the help of Justice Project Pakistan, a human rights organization, to request that the state help facilitate the return of their loved ones’ remains.[161] The High Court dismissed their application, and Ejaz and Mustafa’s bodies still lie in an undisclosed location in Saudi Arabia. Mustafa’s father explains, “[W]e just wanted to get their dead bodies so that their children could go to their parent’s graves.”[162]

Today, Bushra and Ali Raza, now aged ten and 11, live with their maternal uncle.[163] When Bushra first returned to Pakistan, she could no longer speak Punjabi, and her family struggled to communicate with her. According to Mustafa’s family, “She was… disturbed… [s]he used to keep silent.”[164] To this day, “[s]he doesn’t want to talk about [what happened].”[165] Bushra struggles to concentrate and is doing poorly in school. Both Bushra and Ali Raza “miss their parents a lot.”[166] The plight of Ejaz Fatima and Mustafa Muhammad is emblematic of the obstacles faced by indigent foreign nationals charged with drug trafficking, particularly where—as in the case of Pakistan—the country of origin is unwilling to provide assistance.

To write this profile, we conducted interviews with Ejaz and Mustafa’s legal advocates and with Mustafa’s family. We also consulted the limited case documents that were available. We publish this profile with both Ejaz and Mustafa’s families’ consent.

Gendered Pathways to Offending

The Role of Economic Insecurity in Pathways to Drug Offending

Economic insecurity: a gendered phenomenon

As women in a patriarchal society, women on death row for drug offenses are subject to gendered systems of oppression that push them into economic insecurity. As Lucy Harry has argued in her study of women on death row in Malaysia, economic precarity is a better framework than poverty for understanding women’s pathways to committing drug offenses.[167] Precarious work is defined as the uncertainty over continuing employment, lack of control over working conditions, wages, and the workplace, lack of regulatory protection, and a low income level.[168] Women, especially women in the Global South, are over-represented in precarious work.[169] Men and women tend to be segregated into different occupations, with women disproportionately in part-time, low paying jobs[170] with short-term contracts or no contracts at all and little opportunity for career progression—in other words, precarious work.[171] This labor market gender segregation is partly attributable to discrimination by employers, who may be less likely to hire or promote women because they expect women to leave the labor market when they have children.[172]

The other key reason for women’s overrepresentation in precarious work is their disproportionate share of unpaid care work: one study estimates that women perform 75% of the world’s unpaid work.[173] Moreover, they are often responsible for providing care and financial support to both their immediate and extended family.[174] This unpaid care burden is exacerbated for single mothers, who make up the majority of one-parent households[175] and face significantly higher poverty risks than average. Single mothers must support their family on a sole income, which is often inadequate, and they often struggle to juggle paid and unpaid work. They also face additional challenges due to their gender, such as pay gaps and motherhood pay penalties.[176] A series of studies from Thailand showed the financial impact of early caregiving responsibilities among women who were later incarcerated for drug offenses. Many faced caregiving responsibilities early in life and had to leave school early either to support their parents or their families—often after marrying and having children as teenagers. These caregiving responsibilities severely curtailed their future employment prospects.[177]

The burden of unpaid care work also makes it harder for women to secure long-term, full-time, well-paying employment. Women responsible for unpaid care work are more likely to pursue more precarious work in the labor market, such as part-time work, so that they have the flexibility to meet their unpaid care responsibilities.[178] In East and Southeast Asia, for instance, young women are less likely than young men of the same age to transition to education, employment, or training after they leave school—even though girls attend and complete school at equal (or higher) rates than boys in the region. The most common reasons that young women in the Asia Pacific region are not in paid employment are family responsibilities, housework, and pregnancy.[179] Furthermore, neoliberal reforms have worsened the economic precarity and financial stressors that women face by making the labor market more precarious overall,[180] and by decreasing the availability of public care.[181] These reforms dismantled social safety nets that “buffered insecurity”[182] and left countries with withered public services, especially in education and healthcare.[183]

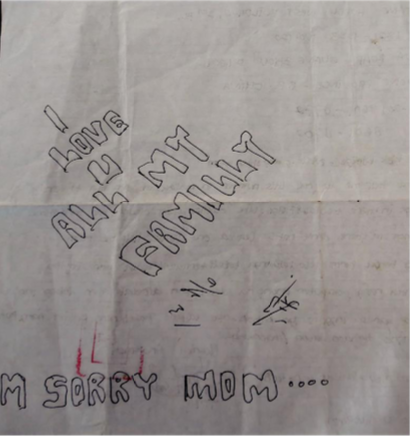

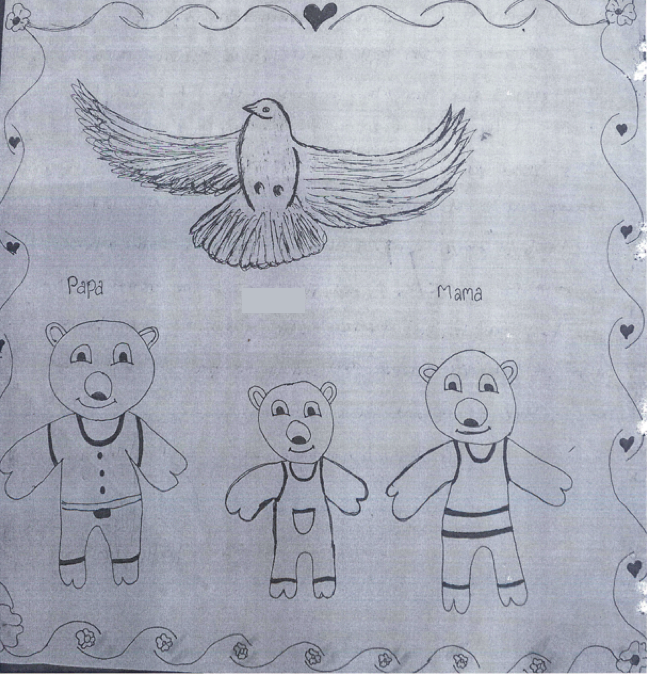

Drawing by a woman sentenced to death for a drug offense in China, sent to her family. Photo courtesy of Komnas Perempuan.

The gendered financial burden of caring for family members, without the aid of strong social support systems or access to stable work, is one of the key factors that pushes women into trafficking drugs. In Malaysia, for instance, a recent study found that many women—especially those who were single, divorced, or pregnant—decided to traffic drugs because they needed money to take care of their family’s needs.[184] We found similar trends in our research on other countries.

The economic precarity of women migrants

Globalization and neoliberal reforms have resulted in increased migration,[185] and women make up an increasing majority of intra-ASEAN migrants in many ASEAN countries.[186] Many women experience gendered pressures to migrate. The families of women—especially young girls—may exercise significant control over women’s decision to migrate, making “the distinction between forced and voluntary migration difficult to identify.”[187] Women often migrate for work to support their families.[188] Some women may also see migration as an opportunity to escape oppressive patriarchal systems by freeing themselves from parental control, making more independent marriage choices, and becoming more financially independent.[189] Women seeking work abroad are especially vulnerable to exploitation by drug syndicates. Many of these women have never engaged in waged work before[190] and are desperate for money because they are struggling financially[191] and are from areas with high unemployment.[192]

Women and economic precarity: a pathway to drug offending

In most of the cases we reviewed for this report, women who received a death sentence for drug trafficking had experienced economic precarity. Lucy Harry found that a majority of women on death row for drug trafficking in Malaysia experienced economic precarity before their arrest.[193] Most of them were unemployed or engaged in precarious work that did not require higher education or significant training—such as domestic worker, bartender, and cashier—before their arrest. Others likely worked in the illicit economy as masseuses or sex workers. Only a handful of women had high-paid, “high-skilled occupations—an accountant, a nurse and teachers.”[194] Most of these women had few viable opportunities to earn money, and drug trafficking emerged as one of their few options. For some women, trafficking jobs present an opportunity to support their families. For others, selling drugs allows them to escape domestic violence or familial abuse.[195] Many women who experience economic precarity, however, feel that they had no choice but to traffic drugs. For example, one woman, who was single and working at a hair salon, accepted a job transporting drugs because she needed extra money to pay for her father’s medical bills. She was sentenced to death.[196] Courts often fail to sufficiently consider these nuances at sentencing, and in jurisdictions with mandatory capital sentencing or presumptions of guilt based on quantity, they are unable to do so at all.

Researchers in Thailand have similarly found that the most common pathway to offending for women was “economic familial provisioning.”[197] Many women in one study shared similar stories: childhood poverty led them to leave school early, limiting their employment prospects. As adults, they continued to face poverty amid growing responsibilities to financially support their parents and dependents. They needed money to afford necessities such as food, utilities, and the cost of sending their children to school. As their anxiety reached a peak, a friend or acquaintance who was aware of their precarious economic situation offered them a job transporting drugs. The women saw the job as a solution to the pressing problem of how to support their families.[198]

Economic precarity makes women more vulnerable to drug traffickers who may exploit them to carry drugs without their consent. A majority of the women whose cases are detailed in our report stated that they were unaware of the drugs they were transporting. Mary Jane Veloso, for instance, thought that she was traveling for a work opportunity abroad when in fact she was used by a network of illegal recruiters to transport drugs across borders. Moreover, women can be vulnerable to drug trafficking recruiters for both economic and social reasons.[199] Some recruiters appear to use both economic and romantic incentives to trick women into transporting drugs. One known trafficker tricked multiple women into trafficking drugs, including an Indonesian woman with whom he started a romantic relationship. He tricked the woman—who was a mother of a young child and undergoing a divorce—into traveling with a suitcase containing hidden drugs. At the time, the woman was merely grateful that he was covering her travel expenses. Originally, that woman’s flight would have taken her to Malaysia, where she would have faced the death penalty if caught. At the last minute, he re-routed her to Hong Kong, where she was arrested and faced a long prison sentence instead.[200]

Drug trafficking does not, however, resolve women’s economic precarity. Indeed, it is important to note that women’s precarity “is perpetuated—not solved—by drug trafficking.”[201] Women often make little money from trafficking; they usually earn significantly less than the value of the drugs they carry, often because they are not aware of exactly what they are carrying.[202] Drug trafficking is, like most women’s jobs pre-arrest, just another precarious job—albeit one that exposes them to the risk of capital punishment.

Drawing by a woman sentenced to death for a drug offense in China, sent to her family. The artist has depicted herself with her husband, and her son, as bears. The bird symbolizes her wish to fly, free from incarceration, to her family. Photo courtesy of Komnas Perempuan.

Manipulative Relationships

Women facing the death penalty for drug offenses are frequently arrested together with male suspects. In many such cases, male romantic partners drive women’s involvement in the drug trade. Yet male co-defendants or co-suspects often face lesser or no criminal consequences for their actions, even if they played a key role in the drug-related activity. Researchers Carolyn Hoyle and Lucy Harry have found that in Southeast Asia, most women face the death penalty for crimes stemming “from their relationships, be it with their dependents, intimate romantic partners, friends, or relatives.”[203]

This section explores the impact of manipulative or coercive intimate relationships on the lives of women who face death for drug offenses, whether that relationship is genuine or part of a scam to trick women into transporting drugs. Understanding how manipulative relationships can lead to drug offending is key in jurisdictions where the law presumes that defendants have knowledge of any drugs in their possession and infers intent to traffic from the quantity of the drugs.[204] Men who fake relationships to trick women into unwittingly transporting drugs rely on a common set of tactics, but female defendants struggle to convince judges that they were not aware they were carrying drugs. Courts also often neglect to consider the role of an abusive or threatening relationship on a woman’s decision to transport drugs.

Available data makes clear that men are considerably more likely to play a role in women’s pathways to offending than the other way around. Lack of detailed data often makes it difficult to ascertain the degree to which a woman experienced pressure, financial encouragement, manipulation, or abuse before participating in a drug offense. Even in the realm of relationship scams, where the scammer’s primary goal is to set up a woman to traffic drugs, it can be difficult to untangle how much of any given relationship contains genuine elements. Either way, romance scams represent a common pathway to drug offenses that many judges appear quick to disbelieve, even when there is substantial evidence of manipulation.[205]

Profile: Anna*

Anna was a middle-aged woman with a large and caring family,[206] who lived in a wealthy nation that had abolished the death penalty. At a time when she was unhappy in her marriage, a stranger messaged her on Skype, claiming to be a Captain in the United States Army.[207]

Unbeknownst to Anna, the Captain was a fake persona created by online scammers.[208] She had previously fallen victim to a different cyberscam,[209] and her name may have been on a ‘sucker list’ used by online scammers to target likely victims. Anna was charmed by the caring Captain who seemed to be a good listener, and she developed feelings for him.[210] Though Anna had not been looking for a new romantic partner, she reciprocated when the Captain expressed feelings of deep friendship and love.[211] The Captain sent her loving, poetic messages:

Our lives have become so entwined, that we simply can’t exist separately anymore, We need each other like springtime blossoms need rain and sunshine…[212]

If Anna ever questioned the authenticity of something the Captain said, he responded quickly with voice calls that reassured her.[213]

Eventually, the Captain sent Anna a photo of himself with a “Will you marry me?” sign, and wrote to Anna:

I do not want to waste anytime anymore, I do not want to be lonely, I have searched my heart… you are not happy in your married life, therefore I want to ask your hand in Marriage.[214]

Anna accepted his proposal.[215]

The Captain frequently pushed Anna to send him money for various reasons and manipulated her emotionally when she refused to do so by ignoring her or sending her accusatory messages:

Sometimes I don’t know how [to] think, is it because you [know] that I love you so much, that gives you the chance to treat me the way you like[?] [If] you sent the money as you claimed why is it that the Company [has] not received [it to] date, why is that you choose to break my heart knowing fully well that I need concentration here in the War Zone? So you want me dead?[216]

Though Anna was living on a minimal income and had little money, she was sometimes able to send him small sums. She did so, for instance, to help him when he claimed he was sending her his luggage in anticipation of moving to start a life with her.[217] When it eventually became apparent that Anna had no more available funds, the scam quickly moved to a different stage—the Captain said that they could finally be together if Anna could do him one more favor.[218]

Anna had communicated with the Captain on a daily basis for about two years when he told Anna that he was eligible to retire and could now marry her.[219] He said that she needed to collect his retirement papers from his Commander in a third country, then return the paperwork to the United States Embassy in her home country.[220] Anna quickly prepared for the trip and flew to the country with instructions and hotel accommodations that the Captain had supposedly pre-paid.[221] Nothing about the trip went according to plan.[222] The Captain told her that his Commander, who was connected to the United States Consulate, would meet her at the airport with his retirement documents, but he did not appear.[223] Anna unexpectedly needed to pay out of pocket for most of her hotel expenses.[224] She found herself low on funds and worried about covering the fare to the airport for her return flight.[225] By the time her return date approached, Anna was sleep-deprived and discombobulated after the trip’s unexpected challenges.[226] Scammers often purposefully use the technique of distracting and exhausting their targets to make them less likely to question the scam.[227] The evening before Anna was to return home, a self-identified “representative” of the Commander appeared with the documents she had been waiting for.[228] He then offered to give her a ride to the airport—solving a problem she had been worried about—and he asked Anna to take a backpack of Christmas presents for his loved ones back with her.[229] She agreed to reciprocate his favor, and when she looked inside the backpack, she saw new clothes wrapped in plastic.[230]