Erica Sheppard: A Teenaged Victim of Rape, Domestic Violence and Discrimination

Table of contents

Case Background

Erica Sheppard is a survivor of child abuse, domestic violence, and multiple rapes who is facing execution in Texas. At the age of nineteen, she fled a violent marriage and sought refuge at a battered women’s shelter, where she hoped to receive counseling and assistance. But the shelter would not keep her. Twenty-seven days later, on June 30, 1993, she followed James Dickerson into a house where he killed Marilyn Meagher in a robbery gone wrong. At the time of her arrest, Erica had three children, was homeless, and was mentally ill. Although Erica had no prior record, she was sentenced to death; the jury never learned about her long history of sexual assault and domestic violence.

Erica grew up in a home plagued by poverty and violence. By the age of nineteen, she had experienced all ten of the adverse childhood experiences that place children on a collision path with the criminal legal system. As a Black girl who grew up in poverty, she had little social support. When she was raped as a child, she had no access to mental health counseling. When she gave birth at the age of sixteen, she was forced to cut her education short to care for her infant. When she sought protection from the police for her husband’s brutal assaults, they did nothing to help her.

Erica’s identity as a Black woman accused of killing a white woman virtually guaranteed a death sentence in Harris County, Texas. Black women have been sentenced to death at higher rates than their non-Black counterparts throughout American history. Her lawyer was inept and inexperienced; he failed to present evidence of the sexual violence she endured and the mental illnesses that followed. At trial, the prosecution accused her of lying about the abuse she suffered, stating that she had “no bruises,” and dismissing it as an “excuse.” In closing, the prosecutor appealed to negative gender stereotypes frequently applied to Black women: “Erica Sheppard may be a woman, but she’s certainly no lady.” Her dehumanization complete, the jury sentenced her to death.

As a Child, Erica Experiences Violence and Rape

Erica’s childhood was characterized by unrelenting poverty and savage violence. Her father was an alcoholic who beat her mother in front of the children. When Erica was a small child, her father abandoned his family. Erica’s mother was also violent and beat Erica and her brother, Jonathan, as punishment for minor infractions. Erica’s mother would require the children to strip naked and then whip them with switches or belts. When Erica was a toddler, her mother often left her and Jonathan in the care of a babysitter named Cookie. Cookie’s boyfriend began sexually abusing Erica, forcing his penis in her mouth. He sometimes made Jonathan watch. When Erica was between the ages of three and five, Cookie’s boyfriend raped her vaginally. Erica still remembers the searing pain that caused her to lose consciousness. When she woke, she frantically tried to clean her bloodstains from the bed in fear that Cookie would punish her for “making a mess.” Her rapist threatened to kill her mother if Erica told anyone about the abuse.

When Jonathan and Erica finally told their mother about the rape, she did not believe them. Instead, she labeled them as liars and never reported the abuse to the authorities. Erica’s brother remembers the frustration he felt when he realized that his own mother did not believe them: “it was one thing for Erica and me to have been physically and sexually abused. But it is another thing when the person who is supposed to love you and care for you does not believe you. It made it even worse.”

In Her Teens, Erica is Raped Again, Becomes Pregnant, and Tries to Flee an Abusive Home

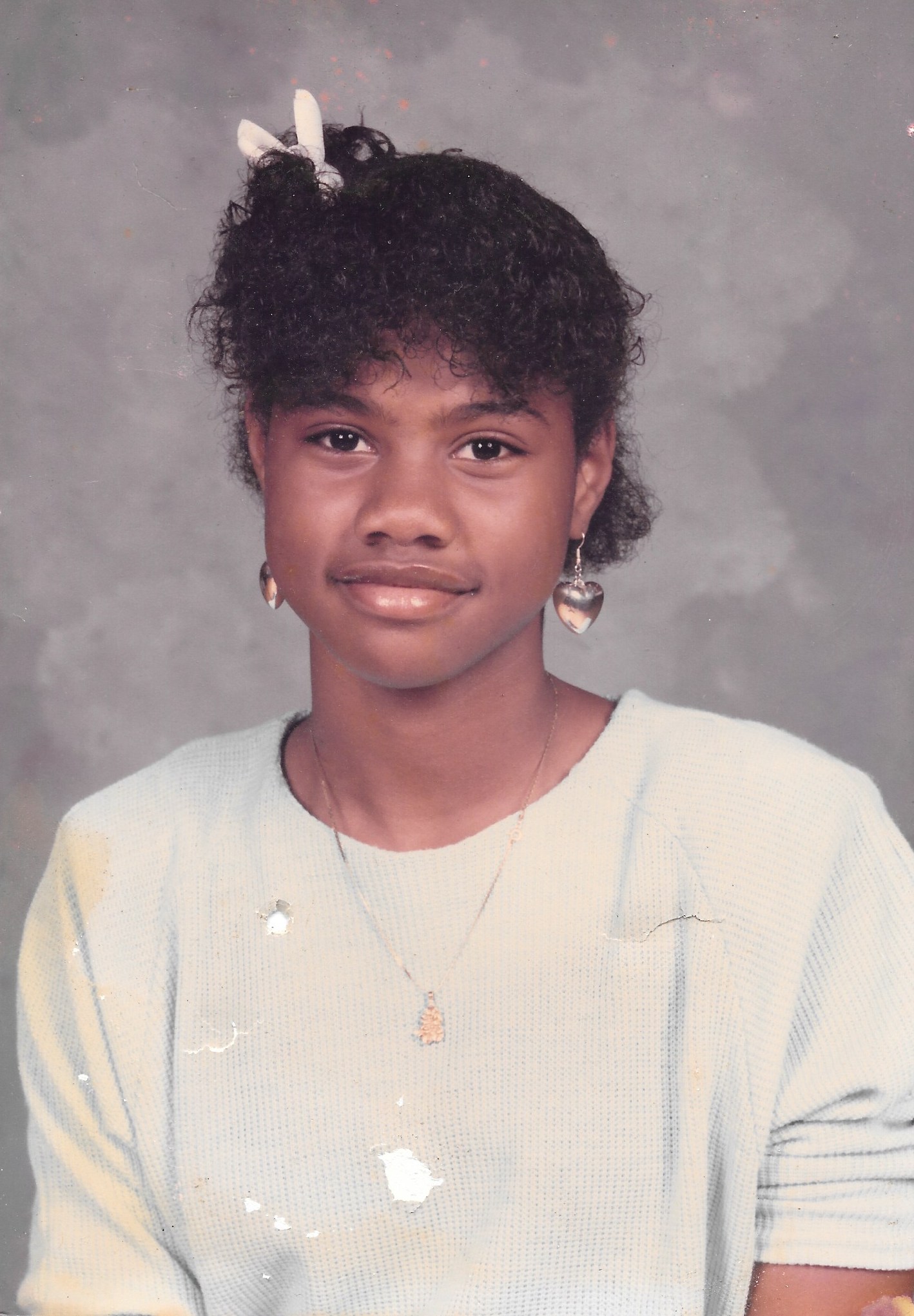

Erica at age 12. By this age, she had been repeatedly raped, and would become pregnant one year later.

The trauma that Erica experienced as a child compromised her mental health. She also has borderline intellectual functioning, and her mental disabilities cause her to be particularly vulnerable to manipulation by others. During her teenage years, older men exploited her vulnerability. At the age of thirteen, Erica became pregnant after an older teenager plied her with alcohol then had sex with her. This was statutory rape under Texas law. Nevertheless, when Erica’s mother heard the news, she beat Erica “half to death,” to the point where Erica thought she would spontaneously abort the fetus. Bruised and fearful, she went to a clinic and had an abortion. She received no counseling or treatment afterwards.

At sixteen, Erica was raped at least three more times. Once, as she was walking to a fast-food restaurant, a man pulled up to her in a car, placed a knife to her throat, and threatened to kill her if she screamed. In a nightmarish replay of her childhood sexual abuse, he forced his penis in her mouth, then left her on the street. Later that year, Erica was at a party, intoxicated, when she was gang raped. One man lured her into a bedroom and assaulted her. As she phased in and out of consciousness, she heard one man tell another to “get some of it.” Erica does not know how many people had sex with her or how she got home that night. On another occasion, Erica was raped by a man named Marcus—someone she thought of as a friend. When Marcus gave her a ride home one day, he asked to use the bathroom, then came into her room and forced himself on her. When Erica became pregnant after the rape, Marcus refused to acknowledge his paternity. And when Erica gave birth to her son Haybert, Marcus refused to help care for the infant.

Without help with childcare, Erica was forced to drop out of high school. Her mother’s abuse had become unbearable, and Erica frequently ran away from home. After her mother attempted to strangle Erica with a phone cord, Erica fled to the Covenant House, a shelter for teenagers, but Covenant House refused to take her in without her mother’s permission (which her mother refused to grant). Three months later, Erica became pregnant again. While pregnant, Erica fled to the shelter a second time to escape her mother’s abuse.

After her stay at the shelter, Erica found temporary refuge with her grandmother, who helped her with childcare and encouraged her to resume her studies. Erica gave birth to her second child, Manchie. She signed up for food stamps and attended classes at the local Adult Learning Center. She applied for and was hired as a secretary to a county judge. For the first time in her life, Erica had some stability in her life and hoped for a better future.

Erica Meets Jerry Bryant, Who Beats Her and Threatens to Kill Her

Erica’s plans for a better future were thwarted when she met Jerry Bryant. He was ten years her senior, and at seventeen, she was easily swayed by his superficial charm. But Bryant was increasingly possessive, jealous, and violent. He began to stalk Erica on her way to work. He accused her of having an affair with the judge and threatened to kill her if she ever left him.

In November 1991, when she was eighteen years old, Erica learned she was pregnant again. One day, when Erica was driving with a friend, Bryant ran her off the road, yanked her out of her car by her hair, brandished the gun he always carried, beat her, and threatened to kill her. Erica was six months pregnant. The violence continued after Erica gave birth to their daughter Audria. Erica remained in the hospital with Audria after the birth (it had been a high-risk pregnancy), and Bryant was incensed that Erica would not have sex with him. Shortly after Erica gave birth, Bryant beat her in a hospital parking lot until she lost consciousness. With blood on her face and a swollen lip, Erica went to the police to seek protection. They did nothing.

Bryant carried a gun and often used it to threaten Erica. Repeatedly, Erica woke to Bryant pointing a gun at her face. When Audria was only a few months old, Bryant accused her of having an affair. When she denied it, he dragged Erica off the couch by her feet, wrapped Erica’s hair around one hand and beat her repeatedly around her face and head with the fist of his other hand. Erica again reported the assault; again, the police failed to arrest Bryant. Instead, they simply referred her to the Matagorda County Women’s Crisis Center.

Erica fled to the Crisis Center with her children in her arms. By this point, Erica was suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder and dissociative disorder as a result of repeated trauma. She had significant brain dysfunction and clinical depression. Nevertheless, she tried to get her life back together. She applied for a new job, attended support groups, and tried to find housing. One day, she learned that she was pregnant with Bryant’s child. Determined not to have another child with him, she went to a health clinic to have an abortion. After the abortion, she did not have a ride back to the shelter and missed the curfew. Erica recalls that when she later returned to the Crisis Center, she was told that she could not stay there as she had broken the rules. Afraid that Bryant would track her down and kill her, Erica headed to Houston to take refuge at her brother’s house. There, Erica met James Dickerson, her brother’s friend.

On June 30, 1993, while Erica and Dickerson were out walking with Erica’s infant daughter, Audria, James spotted Marilyn Meagher entering her home. He told Erica to go with him into the house, threatening to kill Erica and her baby if she did not comply. Dickerson told Erica to get a knife from the kitchen and she complied. Dickerson cut Ms. Meagher’s throat with the knife, killing her.[1] Erica was later arrested with Dickerson and charged with capital murder.

At Trial, Erica’s Attorneys Fail to Present Evidence of Erica’s Trauma and Mental Disabilities

At trial, Erica was assigned a lawyer who was inexperienced and inept; he had never been lead counsel on a death penalty case before. Erica’s lawyer presented almost no mitigating evidence. Judge Carolyn King, a federal appellate judge, described Erica’s life history as so “horrific,” “traumatic,” and “abusive” that it could have persuaded a jury to spare her life. But the defense spent only one hour and ten minutes arguing that Ms. Sheppard’s life should be spared. As a result, the jury never learned about her extensive history of sexual and domestic violence. Defense counsel also neglected to investigate and present evidence of Erica’s organic brain damage and mental disabilities resulting from the physical and sexual abuse she endured throughout her life. At the penalty phase, the defense presented the testimony of one psychologist, Dr. Priscilla Ray. Dr. Ray spent only two hours with Erica and did not interview any of her family members or conduct a clinical assessment of Erica’s mental health. At trial, defense counsel did not ask Dr. Ray any questions regarding Erica’s history of sexual violence and domestic abuse.

In response, the prosecution ridiculed the defense presentation in its closing arguments, accusing Erica of making up the assaults: “Any bruises, any scratches? Any fear? She was not physically abused; but even if she was, what kind of excuse is that?”

Long after Erica was convicted and sentenced to death, her postconviction lawyers retained several mental health experts who conducted comprehensive mental health evaluations. Dr. Myla H. Young determined that Erica’s intellectual functioning is lower than 90% of others her same age. Erica struggles to reason, plan, solve problems, learn from experience, and use good judgment. She is emotionally dependent and passive and is “easily swayed by peer influences.” Another psychological evaluation determined that Erica’s mental age equivalent is 14.9 years old. A third psychologist, Dr. Mark Cunningham, explained how Erica’s trauma and mental disabilities left her especially susceptible to male exploitation and victimization.

Although all of this evidence would have been available to trial counsel in 1995, they failed to investigate sufficiently to obtain and present it. Erica’s harrowing life history remained a mystery to the twelve men and women who held her life in their hands. With no information before them through which to contextualize Erica’s crime or relate to her as a fellow human being, the jury sentenced her to death on March 3, 1995.

After hearing the new evidence marshalled by postconviction counsel, Texas district judge Susan Brown, presiding over Erica’s habeas case, recommended that Erica’s death sentence be vacated, holding that trial counsel had failed to present “evidence that would aid the jury in understanding the connection between evidence of the applicant’s background and character and issue of mitigation.” The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals (TCCA) rejected Judge Brown’s recommendation. Federal district judge Nancy Atlas agreed that trial counsel were ineffective and made clear that she disagreed with the TCCA’s decision, but concluded that she was required to defer to it under federal law. Judge Carolyn King of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit dissented from a decision upholding Erica’s death sentence, noting that “Erica Sheppard was sentenced to death by a jury that did not know that she has brain damage and the cognitive ability of a fourteen-year-old,” and that heard only “isolated snippets of the extensive abuse and trauma that she suffered throughout her life.”

Race Mattered in Ms. Sheppard’s Prosecution

Erica’s death sentence was practically a foregone conclusion in Harris County, Texas, where she was prosecuted and sentenced. Scholars have repeatedly shown that race matters in determining who is sentenced to death across the United States. In Harris County, scholars have determined that Black defendants who kill white people are more likely to be sentenced to death, particularly if the victim is a white, high status female.[2] Professor Scott Phillips—who has studied the influence of race in death penalty verdicts in Harris County—asks: “[w]ould Erica Sheppard have been sentenced to death if she was a white woman who had been accused of killing a low status Black woman? Would Erica Sheppard have been sentenced to death if she had the resources to hire counsel? Almost certainly not.”

During jury selection, prosecutors attempted to remove as many Black prospective jurors from the jury as possible. Before the majority-white jury, the prosecutor then relied on discriminatory tropes to discredit Erica. He used racially charged language to demonize her, calling her a “predator” and a “jackal” who “showed no remorse.” In addition—employing a tactic that has been used against Black women for centuries—the prosecutor explicitly de-feminized Erica: “Erica Sheppard may be a woman, but she’s certainly no lady.” Lastly, he called her a bad mother: “[p]robably the best thing for those children is the fact that Erica Sheppard will not play a role in their upbringing. She will not affect the way they turn out.” Erica’s lawyers failed to object to the prosecutor’s racialized and gendered rhetoric, leaving the jury with the image of a remorseless “predator” as they retired to decide whether Erica should live or die.

Erica Is a Different Person Today than She Was at Age Nineteen

Erica is now 47 years old and has been on death row for 26 of those years. She is physically disabled, experiences chronic pain, and can only walk very slowly with the assistance of a walker. Despite her mental and physical disabilities, she has managed to build a life behind bars. She has maintained contact with all of her children and is now a grandmother several times over. She is no longer the nineteen-year-old adolescent who participated in a crime of violence. Her execution would serve no purpose but to perpetuate the cycle of trauma and discrimination that led to her involvement in the criminal legal system.

[1] The prosecution’s narrative of the events differed substantially during the trial. The state portrayed Erica as the ringleader of the crime based on the statement given to the police by James Dickerson. Erica has consistently stated that Dickerson coerced her participation and that she was afraid of him.

[2] See Scott Phillips, Racial Disparities in the Capital of Capital Punishment, 84 Hous. L. Rev. 807 (2008); See also Scott Phillips, Continued Racial Disparities in the Capital of Capital Punishment: The Rosenthal Era, 50 Hous. L. Rev. 131 (2012).

Case Documents

Inter-American Commission on Human Rights Resolution – Precautionary Measures

Inter-American Commission on Human Rights Press Release about Precautionary Measures

Media & Publications

Stephen Rohde, The Feminist Case for Ending the Death Penalty, Ms. Magazine, Jul. 13, 2021.

Diane Marie Weathers, Praying for a Miracle, Essence Magazine, January 1999.